Leon Wyczółkowski – a workaholic, outstanding artist

Copy of the Birth Certificate, 27/1852, MOB WB 1

The time of artistic activity of Leon Wyczółkowski blends in three important periods of Polish art. It’s over sixty years of the vital presence of the artist, primarily in painting and graphic art, and a half century of constant experimentation, struggling with techniques. He was perceived as a versatile artist, in methods of interpreting a topic and selection of techniques. In addition to oil, he used pastel, watercolor, tempera, and drawing. He was reluctant to artistic expression in one formula and renounced – as he used to say – prescribed schemes. “His activity brought to Polish artistic tradition the factor of continuity and stability. An author of historical paintings and participant of a symbolist breakthrough period, he became an advocate of the idea of

Wyczółkowski had successively succumbed to the influence of Realism, Impressionism, Modernism, Symbolism, and Postmodern Realism, later becoming involved almost exclusively in graphic art, in which he acquired significant skills and recognition, reaching the height of artistry. Berlin critic Alfred Kuhn – with full responsibility – called him the “Rembrandt of lithography.” It is estimated that the Master made between four and six thousand works of art, with graphic art, he probably made much more.

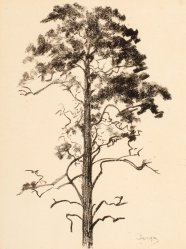

Born in Huta Miastkowska, Garwolin County in the house of his grandfather Jan Faliński on April 11, 1852, according to the Julian Calendar (which was in effect in the area annexed by Russia), on April 24 according to the Gregorian calendar, he spent his early childhood in Podlasie, in the family house of his father Mateusz Wyczółkowski, in Ostrów, in the surrounding of austere nature of meadows and forests, floodplains of the Wieprz River, areas pulsating with the life of birds, fish, in covers of a mysterious fog, frequently falling asleep in haystacks. These mysterious experiences for a child had been a constant inspiration for making many mature works, devoted with love to the beauty of Nature, leaning over its fragile detail (leaf, bark, a bit of frost) and the unusual power of huge, old silhouettes of Polish trees, in particular yew and oak trees, which he practically revered and cherished.

Starting from 1863, he attended a middle school in Siedlce, living with his grandparents during the national uprising. After the premature death of his father and the sale of the estate in Huta Miastkowska, 17-year-old Leon along with his mother who remarried, moved to Warsaw. In 1869, he enrolled in the Drawing Classes, known as “Gerson’s School.” Initially, Wyczółkowski was educated under the guidance of Aleksander Kamiński and Rafał Hadziewicz, becoming finally a student of Wojciech Gerson. Historical paintings were the most popular paintings in Warsaw; painting with a model and plein-air painting were introduced at the third course. During that period, Wyczółkowski painted the following works: The Murder of St. Adalbert by the Prussians, The Defense of Trembowla, Oświęcimówna, Sigismund Augustus with Barbara, St. Casimir and Długosz. The latter painting (which was lost) was displayed in 1873 by the Society for Encouragement of Fine Arts and sold. The same year marked the illegal trip of the artist to the Universal Exposition in Vienna, the episode of enlistment to the army (from which he was released thanks to his uncle for a small fee, paid by his revenue from selling the painting St. Casimir and Długosz), and a trip across the country with Jan Owidzki in the form of “summer studies” encouraged by Gerson, full of adventures and frequently recalled during later talks with Adam Kleczkowski.

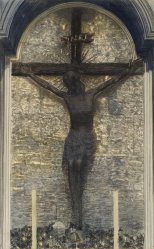

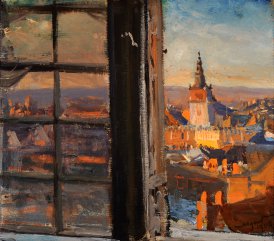

The next stage of development and shaping of Wyczółkowski’s technique took place in Munich (1875-1876) under the guidance of Alexander Wagner (in the spirit of influence of the works made by Delaroche and Piloty). During that period, Wyczółkowski created veristic female studies, for instance A Study of an Italian Woman. From Munich, he moved to Krakow, to Matejko’s master school (1877-1879), and even to his own apartment on Floriańska Street and his studio on Gołębia Street. Matejko’s Battle of Grunwald was being made before the eyes of the young man. Influenced by the Master, Wyczółkowski returned to creation of historical scenes. He painted The Escape of Maryna Mniszech in 1877 (placing the model outdoors); he made a replica of this painting in 1881. He was making “portraits” of architecture of the royal city. He was passionate about looking at Krakow from roofs, towers and other hidden places. He was drawing in detail, “as if he were embroidering” or “knitting shapes with line” of Krakow’s Gothic towers, recalls Maria Twarowska in her fundamental work about Leon Wyczółkowski. In 1898, he made the painting Stańczyk, referring to the image made by Matejko. It depicts a clown accompanied by traitors supporting the invaders. The young artist was in particular fascinated with the Wawel Christ. He was repeating this motif in various types of lighting and different techniques.

It was difficult for Wyczółkowski to surprise audiences with something fresh in art, considering accomplishments of his contemporaries, outstanding Polish painters such as Gierymski brothers, Podkowiński, Pankiewicz, Witkiewicz, Chełmoński, Noakowski, Wyspiański, Chmielowski, Rodakowski, and Malczewski. In addition, famous writers, theater actors, musicians and politicians had a significant impact on development of ideological, patriotic and religious attitudes. We need to mention Wyczółkowski’s multifaceted fascination with Adam Chmielowski, future Brother Albert, whom he met in Lvov in 1879/1880. He influenced spiritually and creatively the whole life of the artist. Painters in Lvov shared a common studio on Piekarska Street, in which they had many talks on fundamental topics. Chmielowski suggested Wyczółkowski how to paint Alina, according to Balladyna by Słowacki, not realistically, but as a legend and myth. They met later in Krakow, where they both painted. On his deathbed, Wyczółkowski was praying to Brother Albert, asking for his intercession in his prayers to God. “Wyczółkowski observed the departure of Adam Chmielowski from the world of art, the group of painters; he saw his spiritual struggles, his wrestling with the angel. (…) But he also saw the dramatic attempts of blending his life into some bigger plan, something that required his obedience to God’s will” – said Jakub A. Malik.

In 1881, “Wyczół” returned after his academic studies to Warsaw. He was painting “salon-boudoir” scenes and portraits for sale. Later, he wasn’t particularly satisfied with some of them. However, during that period (1881-1885) he made a lot of paintings, since he enjoyed making genre studies and landscapes. It should be mentioned that the artist was very critical of his works; he usually destroyed his work and started from the beginning. Apparently only the chosen ones can be distinguished by such humility. The influence of the initial masters on the technique of the young artist are perceived by the “critics” rather schematically, since usually the activity of artists is divided into so-called schools and trends binding in the art of a given epoch. In the case of Wyczółkowski, this matter is more complicated, or even sophisticatedly complex. A clear influence of Gerson left a trace in the “theatrical method of shaping compositions and careful drawing, depicting even miniature details of costume and the way of painting drapery. A shaft of light illuminated the most important parts of the presentation” noticed Jerzy Malinowski. Gerson, remembered by his students, was a traveler with tools for artistic documentation, landscape painter. On the other hand, some of the features taken from Matejko by “Wyczół” included dynamic building of the model, facial expression and gestures, dramatic situation and love to history. However, he had quickly become independent from Matejko, who did not like outdoor painting.

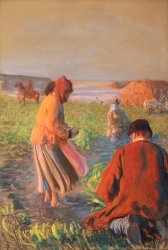

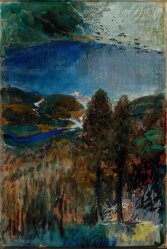

Leon Wyczółkowski had cherished outdoor painting in the Ukraine (his first trip took place in 1883) – which he mentioned many times – as a breakthrough, not only formal, but changing completely the way of thinking and presenting the reality. In 1890-1896, after numerous artistically cognitive travels to, among others, Paris, he started painting in the Impressionist style, becoming fascinated with it. He was creating paintings with the motifs of work, which was very rare among Impressionists. Their most popular topics included idyllic scenes, vedute and urban landscapes typical for townsmen and artists. During that time, the artist had rather surprisingly combined Realism with Impressionism. It is assumed that some inspirations, like for instance in Plowing, were provided by such realists as Rosa Bonheur and Jean-François Millet, as well as Impressionist Max Liebermann. Wyczółkowski’s inclination to careful observation of life with nature in the background, looking at a man working with an animal on agricultural land in full harmony and expression of movement had its origins in his childhood. Therefore, it’s not surprising that he loved the work of people and the scenery in the Ukraine. He was staying there with some breaks in 1883-1894. He worked on his favorite topics many times in various techniques, repeating them in oil, pastels, pencil, and later in graphic art. He created nearly thirty works showing the work of fishermen. Probably during his stay in Vienna in 1873, or maybe later, in 1908, the artist became fascinated with paintings made by Tintoretto, who was painting with color planes. Illuminated by sunlight, natural colors disappear, but colors seem to be applied by sunrays, he was explaining after this enlightenment. The painter’s eye should catch and modify it. He tried to find color “equivalents” of standard colors. Color intensification on canvas had continued until about 1913. It included sapphire blue and dark blue, shades of redness, intensive white and exceptionally blue parts of heaven. The painting Jaremcze made in 1910 was one of his favorites, admired by him after many years, in 1931 in Krakow. This “sunless Impressionism,” as it was described by Teodor Kosch, was the dominant color in the end of the century. “Some pastels made in Jaremcze are an extreme phenomenon in Wyczółkowski’s work on the way of his coloristic searches, making an impression of a distant echo of Fauvism. (…) Later, he toned down his style. (…) Wyczółkowski’s talent as a colorist was unusual, but he wasn’t supported by art culture to the same extent as in the case of Pankiewicz, Stanisławski, and Boznańska,” says Maria Twarowska. Why does she think in this way?

– Probably based on the statement made by the artist himself, who lamented lack of exposure to the world’s masterpieces.

This special “Impressionist” period in Wyczółkowski’s work lasted about six years. It wasn’t in the strict sense pure Impressionism. Jerzy Malinowski, analyzing the new technique of the artist in that period in comparison to the works made by his contemporaries said: “The discipline of paint application by Impressionists was replaced (particularly in Digging Beets) by doctrinal bravado of uncoordinated spots and brushstrokes in the foreground (which can be interpreted as the influence of Postimpressionism) with crucially unchanged, realistic treatment of the background. Therefore, it was a different approach than the one used by Impressionists, who were depicting landscape in full sunlight.”

The authors of the Krakow Catalog published in 2003, Krystyna Kulig-Janarek and Wacława Milewska claim, rightfully, that Wyczółkowski “betrayed Impressionism, not recognizing in many cases direct studies as the final versions of work. Wyczółkowski’s Impressionism was also descriptive; he focused his efforts on realism in depicting people and nature, not abiding consistently by the principles of chromatism, recognizing local colors and using rarely divisionism.” The strength of colors and contrasts, the dynamic method of painting and enriched texture, determine the value of these works on canvas. “Wyczółkowski emerged from Realism, and after studying light and color he stopped to be a Realist. Experiences of Impressionists and his own studies in plein-air painting enriched his Realist’s technique, just like in a later period studies on Japanese graphic art taught the Realist to tone down his expression, which sometimes was reaching an impressive syntheticity of takes” – according to Marian Turwid, a poet and painter from Bydgoszcz. As we can notice, the opinions of critics regarding Impressionist provenance of this period of artistic activity are rather divergent. The Master completed his “sun” experiments in oil (Cows in a Pasture, 1887; Stacks at Sunset, 1892; Kurgan in the Ukraine, 1894; Wading Fishermen, 1891; Digging Beets, 1892; Plowing in the Ukraine, 1892; Sower, 1896) with the painting Fisherman (1896). He naturally continued the Ukrainian topics, but instead of oil he used pastels and graphic art, e.g. Fisherman with a Net, 1908. Impressionistic influences also can be found in the lithograph Digging Beets made in 1911, which is in the Bydgoszcz collection. Biographers note that starting from ca. 1890 the painter was also interested in Symbolism, rooted in the history of Poland. At the “Zachęta” Gallery in Warsaw he showed Fossilized Druid from 1892-1894, related to the tragedy Lilla Weneda by Słowacki. The broken strings of the lute surely symbolize the independence lost by the nation. This work preceded a series of depictions of gravestones of Polish rulers – Casimir the Great and Queen Hedwig – painted by “Wyczół” in the years 1896-1898, signed Sarcophagi. For his painting Digging Beets he received the prestigious Probus Barczewski award of the Polish Academy of Learning in 1893. Four years later, he became one of the founders of the Polish Artists’ Society “Sztuka.” He was also a member of the Vereinigung Bildender Kűnstler Österreichs-Wiener Secession. These memberships resulted in numerous collective exhibitions of the mentioned organizations and his rising popularity. In 1898, the Master became briefly artistic manager of the “Życie” magazine, which ended in disappointment and financial losses.

In 1895-1911, Leon Wyczółkowski worked as professor in the Krakow School of Fine Arts, which was renamed Academy in 1900. He served as its rector in 1909-1910. Wyczółkowski had lived in Krakow until 1929. In the Krakow studio of the Master, on Starowiślna Street the piano was the dominating object, played by Artur Rubinstein, Feliks Jasieński – pseudonym Manggha – and others, frequently spontaneously, influenced by the special atmosphere of this place. Wyczółkowski himself was saying that he had seen music in colors, and colors through music, transferring this perception not only to color, but also the form. As a teacher, he was very kind and friendly to students. He helped them financially, and was even asked for loans, knowing they would never be paid off. He was, however, tired with professorship and the atmosphere in the school. He had problems related to bringing nude models to courses. He was affected by reproaches and duels with Piotrowski and Mehoffer, which were not in his nature.

Lighter aspects of then life are reflected by caricatures, preserved in the “Jama Michalikowa” Café and the National Museum of Krakow: Wyczół with Manggha Flying to Japan, Wyczółkowski in Japan, Caricature of Feliks Jasieński and Leon Wyczółkowski, The Duel between Józef Mehoffer and Leon Wyczółkowski, made by Kazimierz Sichulski. There are other enthusiastic memories of other students. One of them was Marian Ruzamski, who claimed that the Master, “leaving his chair, did not leave his students...” From Krakow, he was going to trips on locations in the mountains. He was painting the Tatra Mountains, local people; developed series of works, several dozen works in several months. Frequently, they were immediately sold and later the artist had problems during organization of exhibitions, even collective shows, not mentioning individual exhibitions. He achieved a great success at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1900. At that time, he received the Grand Silver Medal for Portrait. In the same year, he was a guest at the famous wedding of Lucjan Rydel, and the next year he was watching Wyspiański’s Wedding in the Krakow theater. In 1904, he made several dozen mountain pastels in Zakopane, 60-70 paintings. Once again, he received the award of the Polish Academy of Learning for his Self-portrait. In 1905, the artist went with Feliks Jasieński on a long tour across Spain, painting mainly watercolors. In addition, he traveled to Italy in 1907, visiting Florence and Rome.

In 1908, in Krakow, the first School of Fine Arts for Women was founded by Maria Niedzielska, in which Wyczółkowski became a teacher. Courses were attended by Ms. Tyszkiewicz, whom Wyczółkowski had already known. Therefore, the Master was visiting the Tyszkiewicz estate in Palanga in 1907-1908. These travels produced valuable oil paintings, pastels and graphic artworks, featured in the Lithuanian Portfolio. During that time he was painting a lot, including Krakow architecture, portraits, and flowers. In 1909, he went to Gdańsk, followed by Zakopane, whereas in 1910 - to Hutsulshchyna and Bukowina. About 60 works were made there, gathered in the Hutsul Portfolio. After the year 1900, the artist painted numerous landscapes, often with mountain motifs. Leon Wyczółkowski used to disappear from his studio for a certain period of time to go to distant mountain peaks, to Lake Czarny Staw, to the Tatras, the next plein-air after the Ukrainian locations. However, more and more often he used pastels. The final choice of pastels resulted not only from his temperament, but also from the artist’s allergy to oil paints. He worked a dozen or so hours every day. He even didn’t want to eat meals in order not to lose anything from changing illumination, the pervading atmosphere, and he absolutely paid no attention to discomfort. The series from the “Tatras” indicated evolution of painting in the direction of expressionist abstraction, whereas The Tatra Legends made in 1904 are the continuation of the artist’s historical and post-Romantic awareness – just like: the Wawel Christ, 1896; Wieliczka Salt Mine Chapel, 1896; Sarcophagus of St. Stanislaus at the Wawel Cathedral, 1907; Wawel from the side of Zwierzyniec – winter, 1910; View of Wawel with Sigismund’s Chapel in the winter, 1914.

In 1907, the artist was making pastels depicting the most precious treasures of the Wawel Treasury in the series of cartoons: Wawel Treasury. Wawel was important for the artist in that time due to its ancient and present history, as well as the nearby, monumental, bewitching mountains, documented in: Mnich on Lake Morskie Oko, 1904; View of Lake Morskie Oko from Lake Czarny Staw, 1905, and others. Over the years, the “mountain” works underwent formal changes; however, we won’t find close analogies among numerous works of other artists painted at the beginning of the century. In comparison with these works, they are an exceptional group. “By means of not large segments of landscape the artist managed to create references to entire nature and its transcendental dimension,” said the mentioned authors of the Krakow catalog. The reference to transcendence mentioned above will appear with a great strength of expression in the later period of the artist’s works in graphic art, in his depictions of the sky. The artist’s fascination with the immensity of the sea, the mystery of the sea horizon, the vastness of fields and trees is confirmed by paintings and watercolors from the period of his stay in Palanga, Hel and Gdańsk. The works painted with the use of different techniques, including “Japanizing,” in spite of little format, create the feeling of the limitless element. Wyczółkowski liked painting himself against the background of the Baltic Sea and the Vistula River; he depicted the Vistula in different parts of its course. Characteristic of him were patriotic accents blending with the open air, such as the standard with the emblem (The Vistula – Landscape and a Flying Standard), and the importance of national heroes emphasized symbolically (The Funeral of Słowacki on the

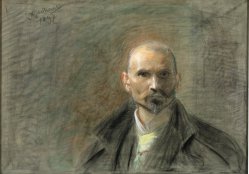

For the posterity, there are valuable are numerous preserved self-portraits from different periods of the artist’s life. The most famous ones include: pastel on paper from 1897, color fluoro-etching from 1904 following the earlier pastel self-portrait with the red coat in the background of the Ukrainian steppe, watercolor painting on paper from 1912, ink on cardboard from 1927, Self-portrait on the Sea made in 1925, Self-portrait against the Background of the Vistula made in 1931 – from a side different than usually. There are different versions of self-portraits on the Vistula River and the Baltic Sea. An intent observer will notice that it was very important for the artist to leave behind his image as rather “not flirting” with the audience. The self-portraits made in the 1920s, painted in the evening of the artist’s life, bring emotional calmness, emanate with seriousness and concentration. Once vivid colors fade, and finally they are replaced with achromatic colors – black and white – in which the artist handles his last self-portrait. He portrayed many eminent personalities, e.g.: Portrait of Jan Kasprowicz, 1898 (oil); Portrait of Stefan Żeromski and his Son, 1904 (pastel); Karol Estreicher in a Theatre Box at the Premiere of “The Wedding” by Wyspiański, 1905 (pastel); Portrait of Józef Chełmoński made in 1900 and 1910 (pastels); and Portrait of Erazm Barącz, 1906 (pastel) and 1911 (tempera, gouache). He painted Juliusz Kossak two days before his death, “documented” famous women, including Natalia Siennicka-Duninowa, Idalia Pawlikowska, Zofia Cybulska – every lady was in a costume harmonized with her spirituality. Works were made at a fast pace, distinguished by perfect capturing of the model’s features.

Sometimes, to emphasize the individuality of a given person, he added attributes of their professions or their favorite objects, e.g. in the portraits of: professor Ludwik Rydygier from 1897 (with assistants), rector Konstanty Laszczka in the years 1901-1902 (with sculpture), professor Karol Olszewski from 1905 (in the chemical laboratory), and Feliks Jasieński from 1911 (in a Japanese costume). Among the portrayed persons, we can find not only famous and great ones, but also rural girls, peasants, highlanders – necessarily wearing folk costumes, in the binding Young Poland style. Wyczółkowski considered documenting Polishness to be his patriotic duty. This leitmotiv is perceived in various depictions: landscapes, architecture, and religious topics. In addition, his flower studies enjoyed great popularity. They were usually custom made.

He never studied sculpture, which he regretted; however, he made several attempts in this field. In 1893, based on a clay model made by the artist, two bronze casts were made – the bust Natałka. While working on the series Sarcophagi in 1895, he prepared two haut-reliefs: Queen Hedwig and Casimir the Great, and along with Konstanty Laszczka, who ran a sculpture studio in Krakow starting from 1899, he prepared a plaque in 1900, as a gift from professors for the Jagiellonian University, put up on the wall at Collegium Maius for a jubilee. His friendship with Laszczka resulted in many portraits with both of them, just to mention Self-portrait with Konstanty Laszczka made around 1901, reflecting their jovial nature. In 1904, he made a sculpture depicting a hussar – The Knight on the Horse – gypsum, polychromed cast, proposed as a project for a monument commemorating Matejko. Due to the lack of financial resources, this project failed.

In 1911, Wyczółkowski returned to the Ukraine, where he made numerous versions of Digging Beets in various techniques, more landscapes in Jaremcze, and sketches to graphic portfolios, whereas in Zakopane, he was supplementing his portfolios of Lake Morskie Oko and Lake Czarny Staw. That year – despite serious disease and retirement – was also marked for its high number of portraits of well-known art collectors as well as such portfolios as Wawel I and II and Self-portraits. Wyczółkowski spent the summer of 1912 on the seaside, recuperating. In 1913, he went on a long trip to England, Scotland and Ireland, via the Netherlands, visiting all major museums. A year later, he was touring the galleries of London, the Hague, Amsterdam, and Rotterdam. He was particularly impressed by the paintings of Jan Vermeer van Delft and William Turner. He returned lost in thought … Later, he planned changes in his technique. After his return, he traveled to Zakopane.

In August 1914, during the outbreak of the war he was staying in the Minsk region, from which he managed to move to Warsaw, where he stayed until the fall of 1915. The artist mentioned his depression experienced due to the threat to his homeland. From Warsaw he returned to Krakow and set out to the mountains. In March 1916, he became a war painter of the Polish Legions. He was assigned to the Headquarters in the winter camp of the Polish Legions in Volhynia, where he stayed till June of that year. It resulted in production of a portfolio entitled Memories from Legionowo. On November 29, he married his housekeeper Franciszka Panek in St. Florian’s Church. In December he participated in the funeral of his friend and spiritual master Adam Chmielowski.

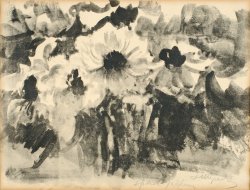

That period was followed by trips across the country, to Zakopane, Kazimierz nad Wisłą, Lublin, and Białowieża. He was more frequently displaying his works in the country and abroad, participating personally in some shows. After reaching his own coloristic “peak,” he toned down the color. He was increasingly fascinated with drawing. “Wyczół” admired Giambattista Piranesi for the distinctiveness of genre. Inspired by Feliks Jasieński, Wyczółkowski became fascinated with Japanese art with its subtlety of forms and colors. New aesthetics was originally expressed by the passion for Japanese and Chinese details, kimonos, screens, tapestries, and porcelain. The paintings A Japanese Woman, 1897 and Still Life with a Vase, 1905 charm with their delicate and bright tones. Plant motifs appeared in plant studies, including Marsh Marigolds, 1903 and A Bush in Autumn, 1904. In addition to compositions with frugal expression, such as Poppies, 1904, the artist was drawing with pastels bouquets in vases saturated with color, against the background of fabrics: Chrysanthemums in A Vase, 1908; Phloxes in a Vase, 1908 and drape patterns: White Roses, 1909; Orchids, 1908; Orchids, 1910, and after 1910 - watercolors: Still Life with a Samovar, 1911; Still Life with Oranges, 1912. As early as 1878, during his first visit to Paris, “Wyczół” was admiring Japanese Art at the Universal Exposition.

There were several exhibits from the Far East, including Japanese woodblock printing. Another Universal Exposition, which he attended in 1889, featured equally attractive Japanese objects, admired by Wyczółkowski. The artist became an avid art collector. His private collection included Japanese woodblock prints, ceramics and fabrics. In 1922, he donated these treasures to the Museum of Wielkopolska. The gift included Anatolian and Caucasian kilims, old Italian velvets, Japanese silk fabrics, Persian, Baghdad, French shawls, Polish tapestries and kilims, old Asian and European ceramic products, Persian and Chinese vases and bowls, unique crystal glass, historical furniture, prayer books, numerous paintings, and graphic art made by such masters as Hiroshige and Hokusai with thirty six views of Mount Fuji. Initially, he tried to express his fascination with Eastern transience and ethereality in pastels. Consecutive “Japanizing” attempts appeared successfully in graphic art. In some works one can see associations with Art Nouveau (Camellias with a Chinaman) and post-impressionism (Digging Beets). Important influences, inspirations and impulses from the painter’s numerous travels produced exceptional works. These surely include Spain, Ukraine, and Hutsulshchyna.

Wyczółkowski had painted fewer oil paintings; until 1912, about two paintings a year, followed by a long break in oil artworks. “Wyczół,” however, returned to oil in order to commemorate Brother Albert, a friend, whom as we know he met in Lvov in 1879/1880. The artist made two oil paintings of Brother Albert, in 1932 and 1933, although he did not finish the second one.

From the beginning of the 20th century, the artist took interest in graphic art, and then devoted himself almost exclusively to it. At first, he was involved in oleography, aquatint and fluoro-etching, in which he depicted subjects previously presented in oil and pastel. Wyczółkowski learned about fluoro-etching technique and its technical aspects, as a Polish invention, from Tadeusz Estreicher in his studio. Later, he worked on metal engraving and etching techniques, and algraphy. Finally, the Master found himself in lithography. After these experiments, he used to say to his friends: “…my graphic things will remain. I pay more attention to them than to all my paintings.” Until 1922, his graphic portfolios contained primarily autolithographs, combined sometimes with fluoro-etching and autoalgraphy. The artist was changing his way of operating the chalk, adding ink and applying some watercolor. He usually was preparing lithographic stone and trial prints himself, choosing texture and shade of paper, and coloring. He was preparing up to thirty prints, after which he was destroying the stone.

In 1902, he made a graphic artwork – aquatint self-portrait with an inscription “To Feliks Jasieński - L. Wyczół, the first graphic work d 19/5 902” It seems that Wyczółkowski was not happy with his earlier attempts, since his first dated graphic artworks are color oleographs made in 1901. In 1903, Wyczółkowski donated several color lithographs to the Portfolio of the Association of Polish Graphic Artists, published in Krakow thanks to the efforts of Jasieński – 4 charts. It was followed by production of the so-called Mixed Portfolio, 1904 – 7 charts, independent, although not monothematic; fluoro-etching, single- and multicolor lithographs as well as the following thematic, independent portfolios: 1906 – the Tatra Portfolio – 8 aquatints – Krakow 1906; 1907 – the Lithuanian Portfolio, 25 autolithographs and autoalgraphies, Krakow; 1908 – the Gdańsk Portfolio, 20 autolithographs, Krakow; 1910 – the Hutsul Portfolio, 29 lithographs, Krakow; 1911/1912 – the Wawel I, Wawel II Portfolios, 18 lithographs, Krakow; 1912 – the Ukrainian Portfolio, 19 lithographs and 1 autoalgraphy, Krakow; 1915 – the Old Warsaw Portfolio, 7 charts, Krakow; 1915 – the Krakow Album, 12 lithographs, Warsaw; 1916-1920 – the Memories from Legionowo Portfolio. 1916, 19 autolithographs, Krakow; 1918/1919 – the Lublin Portfolio, 20 (17) autolithographs, Krakow; 1922 – the Impressions from the Białowieża Portfolio, 10 lithographs, Krakow; 1923-1924 – the Gościeradz Portfolio, 5 lithographs, Krakow; 1926-1927 – the St. Mary’s Church Portfolio – Jubilee Portfolio of St. Mary’s Church in Krakow , 10 single- and multicolor autolithographs with a cover, Krakow; 1931 – the Impressions from the Pomerania Portfolio, 8 lithographs, Poznań, as well as individual graphic charts, including noteworthy and significant (subjective selection) ones, diverse in theme and technique: Wawel Christ, The Madonna in Rainbows, Sigismund Chapel Gateway, Inside the Wawel Cathedral, Town Hall in Kazimierz nad Wisłą, Szymon Tatar, graphic portraits of Feliks Jasieński, Erazm Barącz, Alfred Cortot, Tadeusz Żuk-Skarszewski, Kazimierz nad Wisłą, Kościuszko Mound, Still Life with a Decanter and Flowers, two charts Anemones, Primroses, Oak amidst Young Trees, Oak in a Blizzard, Sędzielina, Oaks in the Sun, (a chart with three oaks was awarded with a gold medal in Paris), charts of Rogalin oaks, yews in Wierzchlas, trees and flowers from the Gościeradz park in a spring, summer and winter attire, Oak in Nowy Jasieniec.

The above-named loose graphic charts do not exhaust the complete list of achievements in this field. Some works have been preserved with pithy comments of “Wyczółek,” which are worth familiarizing with while contemplating specific works, for example: “Anemones in a Crystal Glass, cut, in order to emphasize the crystal glass [1925]. Anemones, craftsmanship… I have achieved a lot as regards technique, using the brush only once. In graphic art, I struggled with different techniques, interesting drawings. Finesse and strength. Sometimes, coincidence plays an important role. On Japanese paper, very strong things. How not to be a graphic artist if one gets such results.”

The graphic artworks of Wyczółkowski differ very much from the outstanding works in this field of his contemporaries. The artist sometimes brought out the form in relief and sometimes flattened it, differentiating light and materials, deforming, sifting shadows. “Colorful” is first of all the first period of his graphic activity, and the second one starts in ca. 1912, when the master changed colors mainly into brown and gray shades, and dyed paper played a separate role in his works. The beginning of the third period dates back to the years 1921-1925, color almost disappears, ranges of tones, halftones, achromatism; in his technique, all previous experiences and additionally introduced textures are reflected. He appreciated his cooperation with Władysław Werdeker, which started in 1924. This printer and lithographer helped him tremendously in copying lithographic charts. Werdeker regarded “Wyczół’s” studio as a temple. In his memoirs, he wrote: “One would be mistaken thinking that by hiring me the master required some special, professional assistance from me. He was a brilliant Master of graphic art, artist and printer; many experienced professionals would envy him the way he made his own prints. His age and a long struggle with the lithographic stone had to exhaust his physical strength; it was the only reason he asked me for assistance.” The year 1921 was the jubilee year, marking the fiftieth anniversary of his artistic work. On this occasion, Wyczółkowski was awarded with the Order of Polonia Restituta, 4th class, becoming member of the Order Chapter and an honorary member of the Society of the Friends of the History and Historic Sites of Krakow.

The act of granting the title of honorary member of the Society of the Friends of the History and Historic Sites of Krakow, 1921, MOB Wb. 189_5

Several prestigious national exhibitions were organized to celebrate the artist. In 1922, as it was already mentioned, Wyczółkowski donated his extensive collection of paintings and Eastern artworks to the Museum of Wielkopolska. He used his earnings to purchase a manor house in Gościeradz, Bydgoszcz area. He was spending summer months in it. However, he spent part of the summer of 1923 on the seaside in Dębki, traveling later in summer months to Rogalin, Sandomierz, Tarnobrzeg, and the surrounding area. In 1925, he received the honorary diploma of Zachęta for the Portrait of Poland and the Medal of Honor and Gold Medal in Paris for Anemones and Young Oaks. In addition, he was commended in 1928 and 1929, when he was presented with another Probus Barczewski award for his drawings of Sandomierz and the Commander’s Cross with Star of the Order of Polonia Restituta. He was also awarded with Grand Gold Medal at the Universal National Exhibition in Poznań. Wyczółkowski left Krakow in the beginning of November 1929, moving to Poznań, “since it is closer to Gościeradz.”

Our nation’s capital honored the Master with the art award of the city of Warsaw; the ceremony took place in the City Hall on May 3, 1930. The same year he was very busy during vacation, traveling from Warsaw to Sandomierz nad Wisłą. Later, he was driving with Kazimierz Szulisławski to explore Pomerania. He was coming back to Gościeradz, from which he traveled to Koronowo and outdoor locations.

Architecture was Wyczółkowski’s another great interest and topic of his paintings. There are attractive motifs of Gdańsk, Krakow and Warsaw, as well as other cities in portfolios, and presentations of monumental trees, combining black and white. Magnificent Sędzielin Oaks, Hoar Frost, Caps of Snow and Rime Frost on single charts are still architecture, but also an individual portrait of a tree with its own soul. The images are supplemented by an immeasurable plan, perceived as a transcendent dimension, like in the Starry Sky. The magic of personal experiencing of the world by “Wyczół” has been preserved in a special way in presentations of endless fields, mountain peaks and – paradoxically – in the closed space of woods, being reflected in portraits of human faces and figures illuminated by the omnipresent sun. In the final stage of his work, the artist was expressing his admiration of nature in an unusually succinct way. This reduction in works results in a unique power of expression.

He was complaining to his friends that they demand fourteen copies of every lithograph to libraries, when he was making only several of them. Many portfolios ended up in Krakow, in the department managed by Jasieński named after Wyczółkowski and containing his artworks, whereas the magnificent graphic works, particularly from the last period of his career, are in Bydgoszcz.

“Wyczół’s” studio, featuring mobile easels on rails called the “tram” had already been admired in Krakow, and later in Gościeradz. When both of his hands were occupied, he was giving commands to his servants Władek and Frania, his later wife: “go,” “stop” or was giving numbers of paints and pastels that he needed. He was painting very fast, alla prima, making an impression of a “surgeon during surgery” at the easel.

The decision regarding his departure to Poznań in 1929 surprised everyone. It appeared that the artist decided to effectively move away from the hustle and bustle of the big city and relax, but also work diligently in his manor house of Gościeradz, which resulted in unique works in graphic art. He was seventy when he received the manor house in Gościeradz. In the beginning, he was spending there several months in the summer time. In 1924, he closed his Gościeradz portfolio consisting of five lithographs, where spruces reign supreme; trunks and their snow covered crowns, and in 1931 – the Impressions from Pomerania portfolio, containing eight lithographs.

Artur Marja Swinarski placed the following dedication in the form of a poem in it:

“To Leon Wyczółkowski

It is artist who wins countries rather than soldier in fierce battles!

Mickiewicz won Lithuania calling it

Thanks to you Griffin is associated with the White Eagle:

You have won Pomerania for Poland.”

The University of Poznań donated the Pomeranian Portfolio to Ignacy Jan Paderewski, for which Wyczółkowski received personal thanks from the piano master. The response to Paderewski has been preserved, among many other letters, in the Jagiellonian Library of Krakow: “(...) I am very touched by your words, Dear Sir, since this acknowledgement comes from one of the greatest Poles, who loves his Homeland so much that he dedicates to it his magnificent artistry. The watercolor from Poznań and

Best regards, yours sincerely L. W.” [October 1, 1931]

At the age of 79, Wyczółkowski received a diploma of the member of the Czech Academy of Sciences and Fine Arts, becoming also a Commander of the French Legion of Honor. During the eightieth year of the birth of the Master, several jubilee exhibitions were organized in his honor, in Poznań, Warsaw and Krakow, and once again in Poznań. During that time, he received the Gold Cross of Merit, and was later awarded with the Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta.

Preparing to the Warsaw exhibition, the artist had a dilemma; he had a problem to gather his works that were scattered everywhere. He did not like exhibitions, which he highlighted many times. At the exhibition in the Institute for the Propaganda of Art, organizers were able to show paintings from private collections, three paintings from the Wawel Treasury, as well as graphic arts from private collections; they were exhibited without chronological order. On the occasion of organization of the jubilee exhibition dedicated to him in Krakow, he expressed sadness: “I am a graphic artist, but they skip my graphic art … I will look like a dog without a tail. They want to show graphic art later, as far as I know; they can choose landscapes and architecture – 30-40 graphic things. They hurt me by omitting my graphic art”. In 1932, six works of “Wyczółek” were sent to the biennial exhibition in Venice, which was organized by Mieczysław Treter. They achieved success.

Starting from around 1932, “Wyczółek” was spending most of his time in the country. There were no doors in the house, rooms were divided by drapes, and paintings were everywhere. Marsh marigolds were his favorite topics on easels. It was the last but one stop of his earthly journey.

His last, significant graphic portfolios were created in Poznań and Pomerania. From Gościeradz, he was traveling to various outdoor locations to paint woods and other landscapes. Kazimierz Szulisławski described the new stage in activity of his mate as “light and shadow hunting.” Szulisławski was working as district forester in Różana near Koronowo and in Świt near Tuchola; thus he was an inseparable companion on numerous trips to the Sacred Grove. “Wyczół” in particular revered yew trees, the mystery of legends commemorating them, and history. He claimed that the only thing that is missing on the bark of these centuries-old trees is the signature of Boleslaus the Brave. He was designing creation of an ancient Slav house of worship on a yew site.

The year 1934 brought more awards and commendations to Wyczółkowski. He became a laureate of the art award of the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment. He wasn’t happy with that award. When he was asked, why? – He responded that the award should be handed to Pankiewicz, although Chełmoński was closer to him, as the most Polish painter. He was also presented with the Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta and the honorary diploma of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts. In the same year, Wyczółkowski was offered to chair the Graphic Art Department in the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. He accepted the challenge at the request of then rector Tadeusz Pruszkowski, happy that he had still been able to help young people, as long as his strength allowed. Despite his old age and tiredness, he was always ready to experiment, working diligently. As late as 1935, he made the Pines in the Yew Grove, and in 1936, the unfinished Flowers in a Vase with Two Openings. Therefore, the Bydgoszcz Museum is proud to have in its collection the first and last works made by the artist. In 1935, he was awarded with the Golden Academic Laurel for his accomplishments to Polish art. In the summer, he suffered from sunstroke. He was staying in the Poznań hospital, from where he departed to his beloved Gościeradz. He didn’t work a lot, caught a cold and was weak. A year later, shortly before his death, he received an honorary diploma – as patron – at the exhibition of a new group of artists called “Black and White.” During Christmas in 1936, he stayed in Warsaw, suffering from pneumonia. Szulisławski had immediately left his family and visited his friend at the deathbed, when he was going to the “Great Hunt”. He asked for his students’ works to be brought to his bed for corrections. He told Szulisławski to go back to Gościeradz, being sure that we would soon join him there.

This workaholic died after a serious illness on December 27, 1936 in Warsaw. He was buried in the parish cemetery of Wtelno in accordance to his will, on December 30, on the road, which he frequently traveled between Bydgoszcz and Gościeradz, hurrying to his magical studio with a window overlooking the garden, just like in his ephemeral Spring, dominated by a pear tree called Małgorzatka, reminding the Master a soul lost in a starry sky.

“The art is the greatest religion. Mysticism. A torch, which goes up at a starry night. Human thought, human soul rises to God.” He said this motto in his old age, maybe during the making of his work Starry Sky in tempera (1930).

“Looking at him, I realized that when wonder children appear frequently in lyric, and in particular in music, then in arts there are wonder old men. Such as Leonardo, Rembrandt, Titian, Hokusai, and Leon Wyczółkowski…” With this thought by Marian Turwid, let’s leave a space for reflection on this unique, diligent life and the outstanding, multifaceted work of the Patron of the Museum in Bydgoszcz.

Jolanta Baziak